Red Mother

Into the World - reflections on the Dea Trier Mørch exhibition at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

originally published on In/Out of Practice on 30th August 2019

I just recently got back from Copenhagen for a few days. We celebrated our friend's birthday in a beautiful ochre house in the suburbs, with a lake right at the end of the garden. The long weekend was spent with grass between our toes, drives in the back of a trusty old Mercedes estate, exploring the nooks and crannies of their house (a habit of mine) and spotting tiny baby frogs the size of a thumbnail. I also plunged myself into the Baltic sea, something I've not done for a few years.

We didn't have a lot of time for sightseeing, but the one place we dedicated a day to was Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Opened in 1958, the building and gardens are themselves beautiful, designed by Jørgen Bo and Wilhlem Wohlert in I suppose you could say in typical Scandinavian Modernist style, primarily using brick and warm wood for the construction and large panels of glass facing towards the sea.

As well as temporary exhibitions, they frequently curate their own collection to respond to various questions and themes of the day and to bring new narratives into the fold, something which I don't think many other museums do enough.

I guess I'm a bit of a modernist at heart though, and these days I find contemporary art a bit dissatisfying - I tend to whizz through and take it all in like an experience rather than each work piece by piece, or gravitate towards a few pieces that catch my eye (But for me, none of the art compared to the loveliness of the woven theatre seats in the grand, but still somehow intimate, lecture theatre. I really longed for more design narratives overall. Next time, I'll make a point of joining an architecture tour).

I started out that way with the Dea Trier Mørch exhibition. It was called Into the World and had the face of a cute baby as the hero image, and so I prepared myself for a little bit of an eye-roll commentary about white heteronormative values of motherhood, which so many female artists and designers are often wrongly painted with - I too have my own assumptions when it comes to these kinds of art exhibitions, which I regularly find not least frustrating or contrived, but also dull. But I was pleasantly surprised by what I saw. A small contained exhibition, in what's known as the 'Graphics Wing' designed underground for to protect the works on paper from sun damage, the room is much like a corridor, curving around gently with two main walls for display. As the name (and hero image) suggests, part of the exhibition focuses on Mørch’s

work documenting her everyday experiences of pregnancy and motherhood. In opposition is her work as a committed member of socialist music and art collective Røde Mor, as a political activist creating images for a global platter of issues occurring in the 1970s and 80s.

Suddenly this exhibition became more interesting.

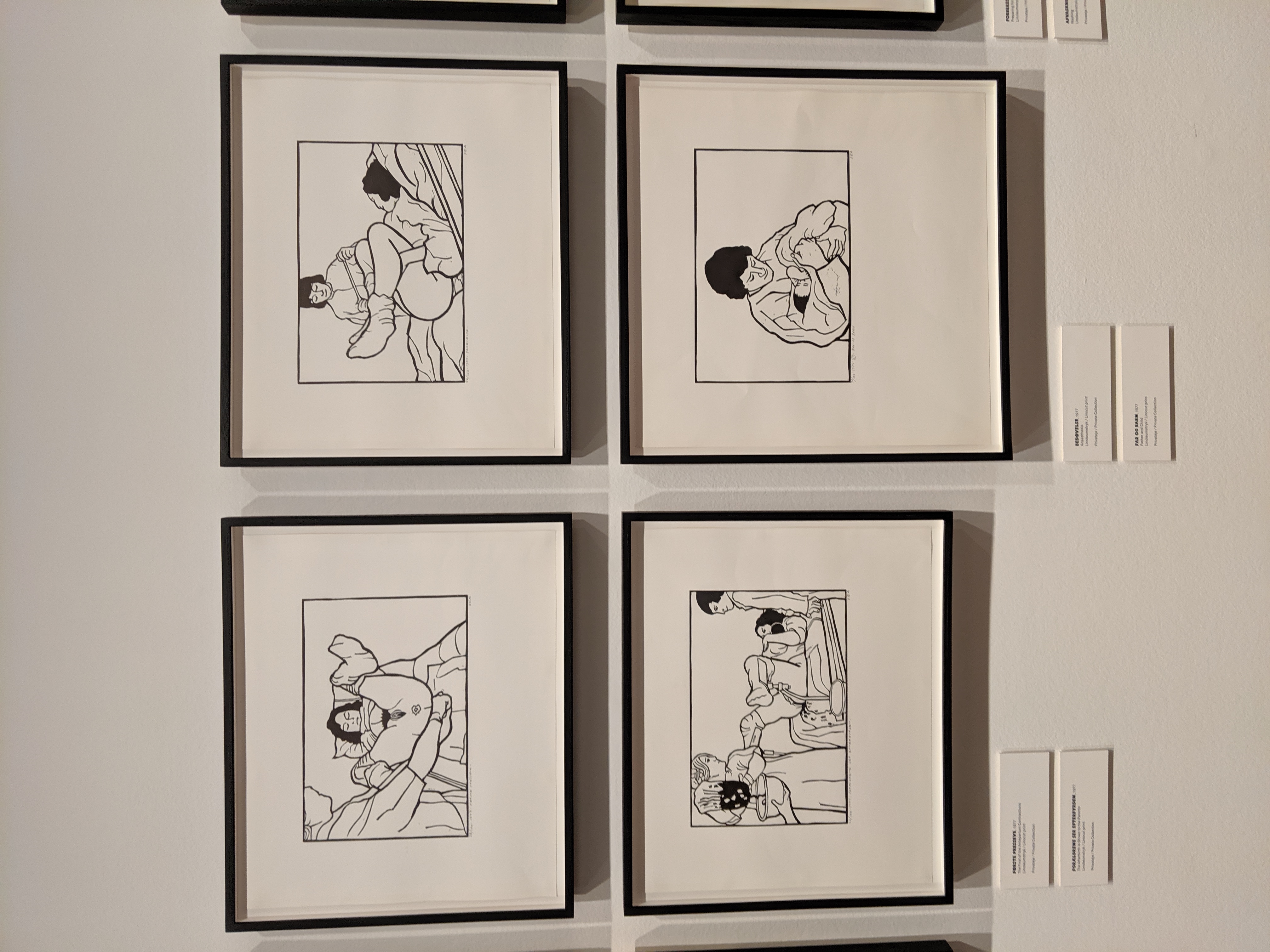

Not only are dedicated exhibitions (books, retrospectives, journal articles... everything!!!) of female designers few and far between, alas, they are almost always shown under the legitimacy of being an 'artist', which still pains me from the Anni Albers exhibition at Tate Modern as amazing as it was. But here shown, discretely but not tenuously, the complexity and tenacity of a female printmaker in the Cold War years, living and working on a less prominent stage, than in other Euro-American places, the icy, scantly-populated Denmark. The star of the show were the original print series of her book Vinterbørn (translated in English to Winter’s Child; 1976). Simultaneously a novel and educational manual, the book recorded her experiences of being in her body and accounts of eighteen other women giving birth at Copenhagen University Hospital. An experience that is still to this day either sanitised, (only portraying the gift of motherhood as the got-it-together mum who can do it all), or the dramatised reality in shows like One Born Every Minute, Mørch's satisfyingly clean and crisp linocuts at the same time did not veer away from the realism of bodily trauma and still taboo full-frontal perspectives of the vulva.

Removed from their role as a housewife, or even as a mother in society, the series focuses on the practical and emotional process of giving birth. Adjacent to this series of horizontal prints, another set of prints simply show the mundanities of being pregnant, the silent moments of mental preparation, staring at the ceiling in bed, watching the nurse clean the floor. Others capture critical intimate moments, the moment a child feeds on a mother's breast for the first time, careful close-ups of the baby's shoulders passing the cervix.

Looking at these prints by Mørch, as a self-identified feminist of the time, they are simultaneously gentle and powerful depictions of women, shifting the narrative to centre women and people with vulvas, and also to make room for a discussion of bearing children outside of women's historic societal role as merely incubators for man's heir. Having the power and agency to bring a child Into the World is depicted and disseminated in Vinterbørn as a mundane, but dignified journey of the female body.

More importantly Vinterbørn is placed amongst posters depicting the world's political plight for democracy, encapsulated by her logo design for Røde Mor, 'a symbol of a humanizing, inclusive approach to the political'. Not dismissed, but rather equal to and a part of her work as an activist, this little exhibition (in spite of it's rather stereotypical front image which I think skews the message to be rather more palatable for the normative gaze) did much to reframe this idea of mothers as multidimensional, inward and outward-looking, and self-aware in their positions of both power and oppression. Becoming 'in the world'isn't just about having bodies that bring life, but also about being in space as a woman and an outsider (Mørch spent extended amounts of time in Eastern Europe covering the Soviet Union), and raising people up who are in further under-privileged positions. Each way of being a mother is as hard, as pressing, as active.

Activism and Motherhood are two things I am constantly having to think about a lot. As a woman in a passing hetero relationship, I am frequently asked if and when I will have children, sometimes in violating ways. I respect that some people have always known they want to have children by birth. But for me, the urge has never been there and I hope that society will quit relentlessly warning against age, regret, or whatever reason others believe vulva-owners should conceive, and kindly accept the first 'thanks but no thanks'.

Activism and Motherhood are two things I am constantly having to think about a lot. As a woman in a passing hetero relationship, I am frequently asked if and when I will have children, sometimes in violating ways. I respect that some people have always known they want to have children by birth. But for me, the urge has never been there and I hope that society will quit relentlessly warning against age, regret, or whatever reason others believe vulva-owners should conceive, and kindly accept the first 'thanks but no thanks'.

Activism on the other hand, is a space that I am still coming to terms with. When I was recently at a conference where a well-respected professor proclaimed that 'historians are activists', I had a LOT of feelings about this kind of self-congratulation.

There is such a status claimed to give yourself the title of 'activist' and I am very uncomfortable with the idea of a bunch of largely white office-casual-clad, middle-aged men sitting in offices believing that they are activists as well as tenured professors in the romantic art of history. While I don't believe academic research mean nothing in this world, to call oneself activist without the receipts does not sit well with me. To be frank, we are not on the front line. We need to be careful about contemporary terminology in the way we are expected to be careful about the ethics and evidence in our historical research.

It's still something I'm working on. But if anything, the exhibition was a reminder - to observe your everyday, to remember what's out there and the people around you, and to go into the world, as a complex, authentic self. In doing so, you are already a mother.

It's still something I'm working on. But if anything, the exhibition was a reminder - to observe your everyday, to remember what's out there and the people around you, and to go into the world, as a complex, authentic self. In doing so, you are already a mother.