Thinking about Charlotte Perriand

'Inventing a New World' exhibition: doing what you want, doing what you can, doing what you know

originally published on In/Out of Practice on 30th April 2020

Preface:

This has been sitting in my drafts for a very long time. It's been a rollercoaster few weeks to say the least. Somehow what I've written still sort of works in the context of now. Maybe I've settled somewhat but its an unpredictable game of how I'll wake up feeling. For now, I think it helps me to reset and return to what I know.

This has been sitting in my drafts for a very long time. It's been a rollercoaster few weeks to say the least. Somehow what I've written still sort of works in the context of now. Maybe I've settled somewhat but its an unpredictable game of how I'll wake up feeling. For now, I think it helps me to reset and return to what I know.

Thinking about this trip makes me think about feeling good and empowered in myself and the world of design. Hoping that that's something we can reach for soon. This was half written in March, and now returning to it at the end of April. I acknowledge it's rather laboured but it might as well go out in the world - if it helps to eek out any heaviness and longing why not.

__________________________________

I've been meaning to write a post on this exhibition on the tail-end of the last one - early February feels so far away now. The unusual, personal high of February (in spite of our idiotic departure from the EU) gave out to a much lower early March, and now, here we are, at the beginning of the European leg of this Covid-19 pandemic, and in the typical British manner, pretending that you'll be fine and everything is fine. Thankfully my uni and supervisors have been taking it seriously from the beginning and so we're now at social distancing until further notice. Even though I have to admit, I've not yet come to terms with working alone at home in a place where I have little social circle, it also happens to be the most beneficial place to be during a lock down.

Somehow, with my particular worlds having to grind to a halt, there is a sense of bittersweet release in knowing that even though I ordinarily have hated this feeling of isolation, at least there is some incentive, some room, to change how I feel about it. I'm excited by the possibilities of finding new ways to connect. As a child of the internet, I am pretty intrigued and fascinated by the potentials of streaming culture, online conferences, support networks and online gaming, but not as brave as the Gen Zs who have this way of sharing braided with their everyday. On the other hand, knowing this will be the way it goes for at least several months, ironically I hope this gives me enough head space to really, truly get offline. Not commuting might allow me to sit still and read real, physical books properly, write letters more often, practice my language learning, draw.

Somehow, with my particular worlds having to grind to a halt, there is a sense of bittersweet release in knowing that even though I ordinarily have hated this feeling of isolation, at least there is some incentive, some room, to change how I feel about it. I'm excited by the possibilities of finding new ways to connect. As a child of the internet, I am pretty intrigued and fascinated by the potentials of streaming culture, online conferences, support networks and online gaming, but not as brave as the Gen Zs who have this way of sharing braided with their everyday. On the other hand, knowing this will be the way it goes for at least several months, ironically I hope this gives me enough head space to really, truly get offline. Not commuting might allow me to sit still and read real, physical books properly, write letters more often, practice my language learning, draw.

The garden has been a saving grace, and watching little seedlings grow makes me forget that I'm actually really anxious about whether I'm capable of a) doing this PhD justice and b) figuring out what I actually want to do.

But in thinking on those anxieties, and with the recent posts going around with the point that going on lock down and doing for example, going to emergency online classes, shows that the ableist world has completely ignored the needs of those who are not able-bodied and/or neurotypical who have asked for these facilitations. It also highlights this capitalist mentality of work - that as long as you are present you get paid. As long as you are useful to the system, you are valid. As long as you do as the system says, then you are rewarded with financial, social and cultural capital, regardless of whether it destroys you and your sense of self. As a funded student, I happen not to come under these terms too severely. And yet I feel trapped in knowing that the work in my future, whether in academia or design, will inevitably be, and I hate that there is so little choice but to comply to this. Somehow there must be a way to break from it.

And how does this relate (at least in my mind) to Charlotte Perriand? Stay with me here, I'm thinking as I type but there is something to this I swear.

But in thinking on those anxieties, and with the recent posts going around with the point that going on lock down and doing for example, going to emergency online classes, shows that the ableist world has completely ignored the needs of those who are not able-bodied and/or neurotypical who have asked for these facilitations. It also highlights this capitalist mentality of work - that as long as you are present you get paid. As long as you are useful to the system, you are valid. As long as you do as the system says, then you are rewarded with financial, social and cultural capital, regardless of whether it destroys you and your sense of self. As a funded student, I happen not to come under these terms too severely. And yet I feel trapped in knowing that the work in my future, whether in academia or design, will inevitably be, and I hate that there is so little choice but to comply to this. Somehow there must be a way to break from it.

And how does this relate (at least in my mind) to Charlotte Perriand? Stay with me here, I'm thinking as I type but there is something to this I swear.

I was really excited to visit the Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World exhibition earlier in Feb. Although I had heard of Perriand before I, perhaps like a lot of people, didn't know much about her and her work. Shame me if you like, but as we know, information on the lives and works of women, queer, and PoC designers are still yet to be explored fully, and have only just started coming to the fore thanks to the often female and/or queer contemporary scholars and researchers. Still their names are not on the tips of the tongue as the names of cis white men. So it's precisely with my lack of knowledge in mind that I was keen to visit, as retrospective exhibitions of female designers don't come around that often, and thinking of myself as a fan of Euro-American Modernism rather than doing it as a scholar, it felt imperative to go, these things are few and far between. I needed a break/wake-up call to remember why I love design and design history so much. After many hours trawling through government documents, I've stupidly forgotten what it means to know and love design (still working on it, but imposter syndrome of trying to be a real 'academic' kicks in often. Currently I don't think it suits me that well - I imagine this feeling is going to happen a LOT in life).

The Louis Vuitton Foundation was a surprisingly spacious exhibition space - from the outside its quite overwhelming, but inside the winged exterior are a mix of both intimate and large enclosures that can adequately display some of the huge wall and furniture pieces. I can imagine curating this exhibition was a challenge, but it was worth it for the huge range of objects and materials, two and three dimensional, things to look at up close and at a distance, spaces needing some natural light and and others requiring more control. Needless to say the exhibition was absolutely thorough, covering her life's work across the board, from architecture, interiors, furniture, policy, research, and her own personal experiments and musings. I was especially intrigued by the fact that there was no explicit labelling of her as any one thing: an artist, architect, designer, furniture maker, etc. Nowhere in the exhibition did they try to pigeonhole her, nor make a big fuss between the various roles she played. Each room quite happily moved from one to the next, drawing out a narrative that I find in monographic exhibitions so rarely - the narrative that a person has multiple hats and relishes in working collaboratively across spheres and communities of people.

Naturally the exhibition starts from the beginning of her career in the 1920s. Like many designers, her work began by transforming and playing with her own spheres: She transformed her own apartment into the 'Bar Sous Le Toit', 'bar under the roof', using stainless steel for the surfaces and furniture, a material dominated by men; photographs depict her androgynous style and Josephine Baker-inspired haircut. complete with a drawing and hanging wire portrait of the dancer; contained in a box alongside, as if floating, is Perriand's infamous ball-bearing necklace, symbolising 'her adherence to the twentieth-century machine age'. Immediately one gets a sense of her attitude towards design and the design world - She seems unintimidated by the modern, but decidedly masculine, world emerging in the new age of aircraft, cars, cinema and mechanics, and quite happy to take on the competition.

In 1927 she rejoined the atelier of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret to form a powerhouse trio of furniture design.

We were met again with the familiar decadent LC2 (after our visits to Corb's digs) under its geometric 2D plan self, and the Chaise Basci also satisfyingly displayed alongside its technical drawings, giving a real sense of how ideas became reality.

Throughout the exhibition there was a real emphasis on recreating spaces. There were several 'reconstruction' style assemblages, constructing entire rooms and floors of buildings, fully utilising the light to give a feel for what the 'new age' looked like. The two earliest rooms could easily fit into an 80s movie scene, shining blue plastics paired with fluffy rich textiles, reflective mirrors and metals with sultry blood-red leather. The interiors later on gradually edge towards more subdued tones and natural materials, but nevertheless allow for surprises and textures.

Throughout the exhibition there was a real emphasis on recreating spaces. There were several 'reconstruction' style assemblages, constructing entire rooms and floors of buildings, fully utilising the light to give a feel for what the 'new age' looked like. The two earliest rooms could easily fit into an 80s movie scene, shining blue plastics paired with fluffy rich textiles, reflective mirrors and metals with sultry blood-red leather. The interiors later on gradually edge towards more subdued tones and natural materials, but nevertheless allow for surprises and textures.

Other displays were more integrated into the space of the exhibition. Dynamic, even cartoonish drawings showing how the set-up was designed to work help you imagine how the seemingly normal desk arrangement could function in action ('Schéma ergonomique du bureau Boomerang', 1938, for Jean-Richard Bloch). But a lot of the furniture themselves encouraged movement in the space, even if you couldn't touch - one long shelf the length of the room followed around the exhibition, helping you imagine what the feeling of the original room might have been like. In spite of the sometimes static nature of the exhibitions like this, especially in furniture displays, there's something perhaps in the naturally uneven grain in the material, or the way each object is shaped and angled, and overlapping each other, that makes it flow. At the same time, Perriand intended the furniture to function as a steady manifesto, a constant reminder of identity and politics. Bloch's staunch commitment to antifacism and dedication to the arts is engraved right into the top of table manifeste, 1937, with two vignetts from Picasso prints Dream and Lies of Franco, two works made shortly before starting to paint Guernica for the 1937 International Exposition.

The exhibition never shied away from pointing out these interwoven networks of players; even captioning Picasso's painted posters of Guernica within the exhibition as the starting point for the woven cartoon modelby weaver Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach, who would become his longtime collaborator. Later on in the exhibition, it further asserted Perriand's personality and agenda to bring people together and question her surroundings. It seems her whole life, in spite of her success as an individual, she was constantly finding ways to collaborate and lift others up - I appreciated that the exhibition unapologetically placed her front and centre, where other institutions might have easily co-opted names like Picasso, Léger and le Corbusier take the limelight, and in fact pointed out her central role in the careers of all these men as director and coordinator of major public projects, as a buyer of great design, and as a mediator between designer and artisan. The Guernica poster was merely one example of how the exhibition unashamedly brought the processes and networks of people behind great works to the fore.

As we venture deeper, the exhibition started to collate the important places in Perriand's life and the ways she responded to those surroundings. Perriand's work from her time in Japan is perhaps some of her most well known, but it made clear to see her transition from Paris to fully leaning into Japanese materials, techniques and cultural preferences. You can clearly see her shift from the spectacular and heavyweight materials of her Parisian days out of art school, shoulder to shoulder with the masculine personalities around her, to finding her own role as design consultant in Japan. The work is comparatively subdued, but not without its own statements. Her experiments layering different materials and methods result in whimsical outcomes; photography of rocks finds their way to feature as table tops, and drawings by local Japanese primary school students take centre stage on a large weaving.

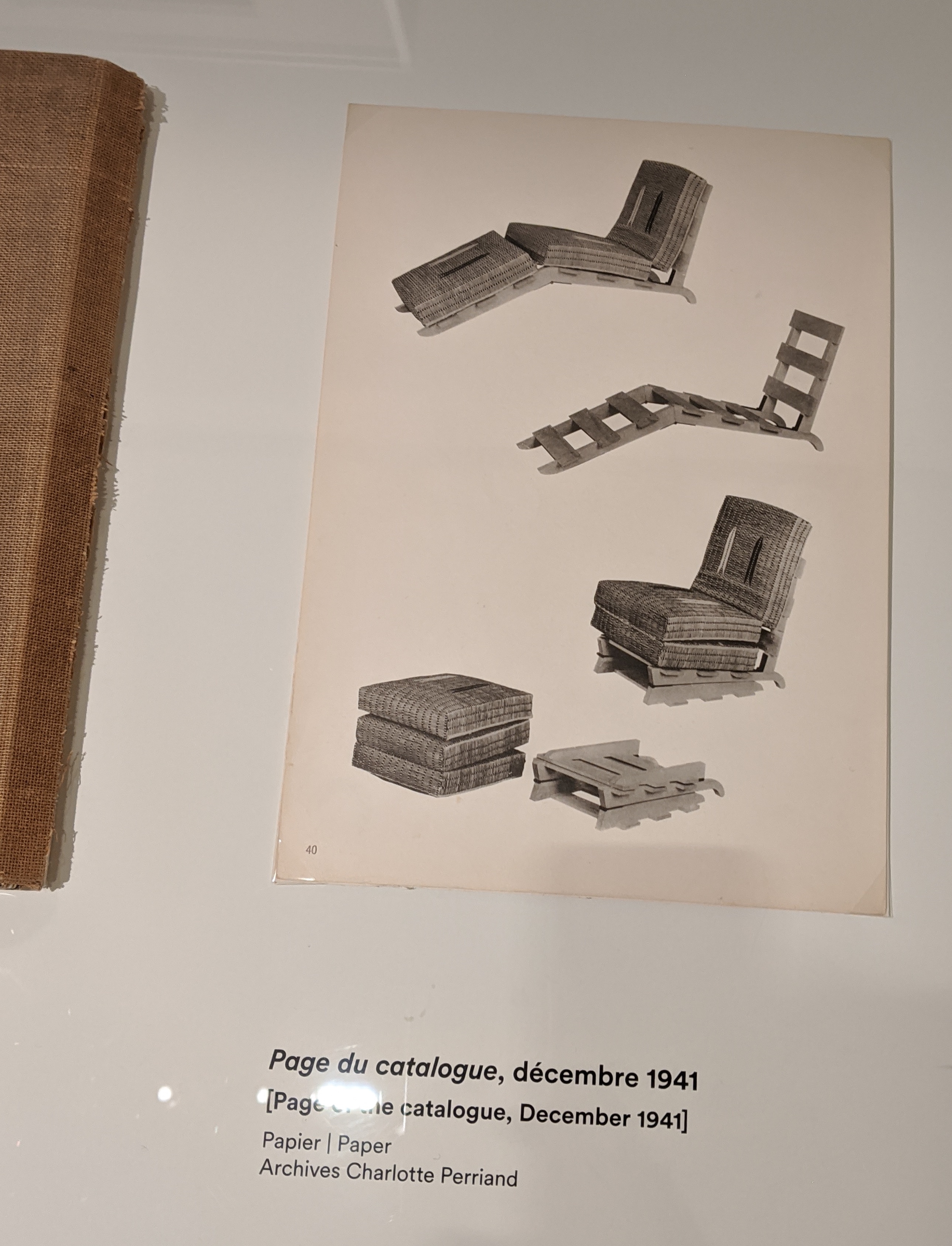

At the same time it seems to challenge the technicality of the material, the furniture tested how much (or rather how little) material could achieve a function. The undulating lines of a surface translated in the bentwood forms, casting clean linear shadows while expressing the curvature of the body on chairs and chaise low to the ground. I particularly loved the strange woven futon chaise, and its graphic interpretation in the catalogue, comparatively clunky to its naked nieghbouring chairs, but still in tune with the materiality of this time and place for Perriand, and full of the intrigue and story-telling that it appears the collection of works seem to evoke.

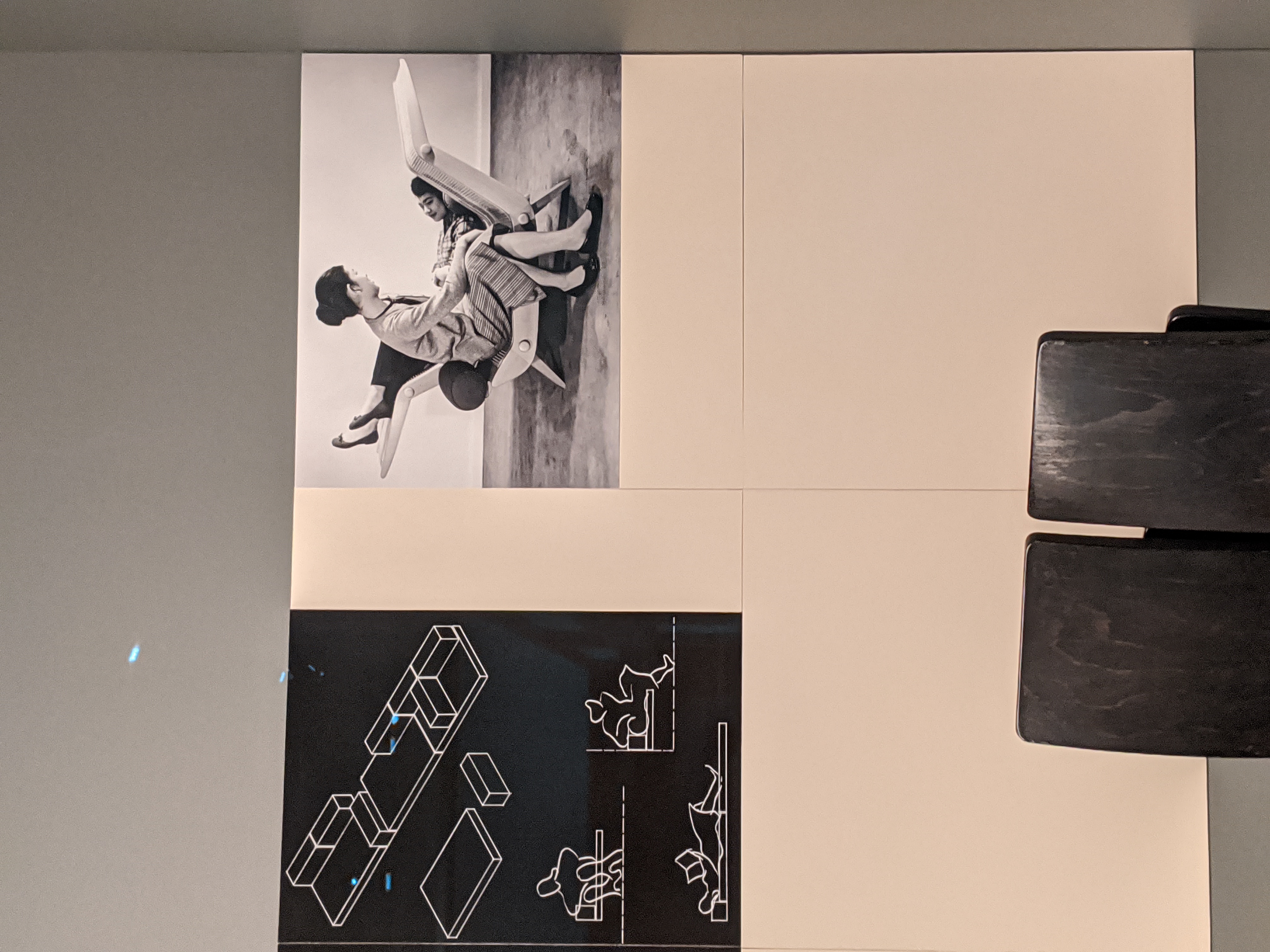

Although only lasting just over two months, her trip to Japan in 1940 was by no means her last. She'd return again in 1955, reviving and revamping the bamboo chaise from her previous trip for the Air France lounge and transforming it into a new modern, cosmopolitan context. She returned with more colour and playfulness, reinterpreting the sultry presentation from earliest tubular steel version,

an anonymous

woman

tilted parallel to the floor, to the posed yet relaxed space between two Japanese women facing each other. I like to imagine she no longer needed to feel the self-consciousness of 'making it' in Paris, instead opting for what seemed right for the project, and fun for herself.

Air France would take her further south to Rio in 1961, where again she draws new excitement from yet another place and new friends. Although a small room, it intrigued me how she was able to travel on her own terms, in spite of the Air France connection through her husband. Here she found agency in cultivating their home, and again exploring a new wood. The shining object in this room was not any of the furniture, beautiful though they may be, but rather the starkly different but for me far more dynamic plan of the Rio table made for the dining room in the house in 1963. The caption read:

'More than 4 meters long, it could seat up to fifteen people. At the carpenter's she became excited by a 6-centimeter thick slab of Jacaranda (Rio rosewood). To respect the grain of the wood, she revised her design by drawing directly onto the wood. This outline was taken as a template to check the suitability in the apartment.'

So to try and piece this all together in my mind, (why the hell does this relate to right now?) but also ultimately I have a sense of longing for that last trip in February, in between weeks of not feeling so great (BoJo happened) and a few weeks before the virus was much closer on the horizon to Europe than Britain assumed.

In an age of such competition, in all field but design in quite a particular way, its refreshing to see one of the female pioneers of European modernism go so boldly. The exhibition probably didn't go into the problems she faced so much, but I can imagine that her actions were seen as greatly radical and out of line with the status quo at that time and I'm sure she suffered for it. Its a great lesson to remember to inject your own confidence and tenacity into the work. No-one else is going to do it for you, and in fact lots of people won't believe in you. But rely on friends, keep them close, share your hardship, your work and your joy.

In an age of such competition, in all field but design in quite a particular way, its refreshing to see one of the female pioneers of European modernism go so boldly. The exhibition probably didn't go into the problems she faced so much, but I can imagine that her actions were seen as greatly radical and out of line with the status quo at that time and I'm sure she suffered for it. Its a great lesson to remember to inject your own confidence and tenacity into the work. No-one else is going to do it for you, and in fact lots of people won't believe in you. But rely on friends, keep them close, share your hardship, your work and your joy.

More and more in this current pandemic, I've thought about the ways I want to live, and the values I want to strive for. Thinking about Charlotte Perriand and this exhibition reminds me to be savvy, but also sometimes, it's everything, imperative, to throw caution to the wind, go out and explore. Get excited. Make statements. Quietly but boldly make your passion known and understood. What I loved about her is that she never settled in one term of herself, leant into the multi-faceted layers in her interests. She committed to people and places and held them dear. If I can endeavour to trust my joys and do what I know, I can only do what I can.